contents

Director

Director's Message

Dissection usually involves human or animal bodies, but here, the objects are man-made. Why do we "dissect" man-made products? In the 20th century, the progress in machine manufacturing technology has resulted in an abundance of mass-produced goods around the world. At the same time, the need to respond to environmental issues such as global warming and waste has become a major social challenge for every country and region. However, it is no exaggeration to say that mass-produced goods are in fact social infrastructure; they are necessities in our daily lives. In order to support the world's population which is growing dramatically in modern times, no one can deny that we need to distribute mass-produced goods efficiently and with minimal impact on the environment. When it comes to environmental issues, we tend to immediately perceive the problems as being smoke billowing from factory chimneys, or mass-produced goods generating a great deal of waste, when in fact, we hardly know what is happening behind the scenes.

After becoming significantly involved in product development and package design of mass-produced goods, one day I came up with a project to dissect things from outside-in from a design point of view. The word design tends to have a strong visual sense, being associated with something that can be seen, such as shape or color; though originally, the word design contains a significant implication of "engineering design." For example, with food, if the taste and texture in the mouth are engineered, then shouldn't those also be considered as design? Once the image of dissecting something came to my mind, questions such as this kept on surfacing; to capture design as a way of seeing things. In other words, I realized that design could be employed as the scalpel in order to understand things and the environment. If design were inherent in all things to some extent, then one should always be able to dissect them relying on design.

When manufacturing becomes a black box and products rapidly become encoded from the perspective of the consumer, it soon becomes difficult to know what is happening behind the scenes. Because consumers don't know what lies behind the scenes, they lose the opportunity to develop feelings of attachment or the inclination to treasure something, causing them to throw away products that are still very usable. Consumers don't even know how the products are processed after being thrown away. Modern society is a place where we have no knowledge of where one comes from and where one is headed. Moreover, since economics is the only indicator of wealth, not only is design often understood as an economic tool, economics and culture tend to be perceived separately. Yet design has the ability to connect economics and culture.

In this exhibition, we pick up products familiar in our daily lives, dissect them from a design point of view, and interpret and display the results. I hope this "Design Anatomy" exhibition succeeds in helping you to develop a keen eye and to see products from an anatomical point of view.

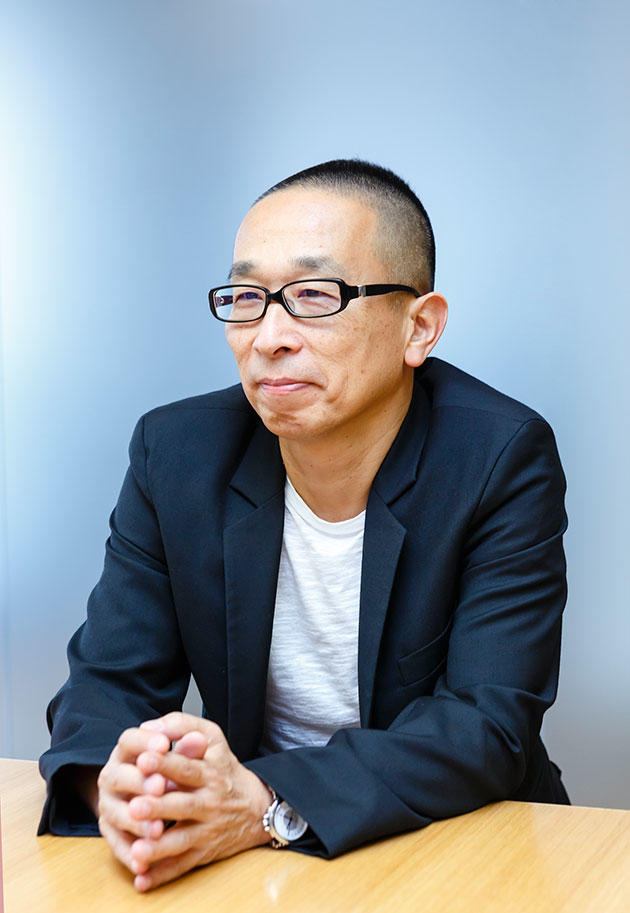

Taku Satoh

Profile

Taku Satoh

1979, graduated from the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music (current Tokyo University of the Arts), Department of Design. Master's Degree completed in 1981. 1984, founded Taku Satoh Design Office after working for Dentsu Inc. Starting from product development for Nikka Whisky's "Pure Malt," Satoh worked on product design for "LOTTE XYLITOL Gum" and "Meiji Dairies' Oishii Gyunyu," graphic design for "PLEATS PLEASE ISSEY MIYAKE," and has also created logos for "21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa", "National Museum of Nature and Science," and "National High School Baseball Championship." Satoh provides overall direction for "Design Ah!" and art direction for "Nihongo de Asobo" (Let's Play in Japanese) for the educational channel of NHK Television, while also serving as Director for 21_21 DESIGN SIGHT among many other projects. He is also author of the books Kujira wa shio o fuite ita (DNP Art Communications), JOMONESE (Bijutsu Shuppan-sha), and a photograph book Maana-Mikan (Heibonsha).